Plaques as Commemoration

In 1914, ‘Lime Kiln Cottage’ stood close to the Bushey railway arches, near the kilns where local chalk was once burned to provide lime. Up the hill towards Bushey village, just beyond ‘The Merry Month of May’ alehouse, was a row of cottages with the intriguing name ‘Crook Log’. Both ‘Lime Kiln Cottage’ and ‘Crook Log’ were demolished decades ago but this year the Bushey First World War Commemoration Project will focus a spotlight on them and other houses in the area as the servicemen who died in the war are remembered . ‘Lime Kiln Cottage’ was home to the Drake family, who lost two sons, and five servicemen living at ‘Crook Log’ gave their lives for their country.

Crook Log

The communities of Bushey and Oxhey in 1914 included wealthy land owners, labourers and railway workers. Some who enlisted for war service lived in grand mansions and others in tiny cottages. More than three hundred and fifty did not come home.

Bushey Manor House

Bushey Manor House, which stood on the site now occupied by The Bushey Academy, was owned by Charles Gabain, a retired French coffee importer, Bushey Urban District Councillor and JP, who lost his only son in the war. Captain William Gabain, who was awarded the Military Cross for gallantry, was last seen in 1918 ‘in a sunken road holding on with a handful of men practically surrounded by infinitely superior numbers of the enemy’. He was reported missing but it was nearly a year before his family accepted that he had died and his obituary appeared in The Times.

Hartsbourne Manor

‘Hartsbourne Manor’, now a golf club, was owned in 1914 by the American actress, Maxine Elliot, who was said to be engaged to a New Zealander, Anthony Wilding, a former Wimbledon Tennis Champion and frequent visitor to her home. In May 1915, Maxine Elliot was working for the Red Cross, the first American to do so. She was travelling along the waterways of Belgium, providing starving refugees with food and medical attention, when she heard that Captain Wilding had been killed in action at the battle of Aubers Ridge in France. The man she hoped would join her permanently at ‘Hartsbourne Manor’ had perished.

Maxine Elliot Anthony Wilding

‘Kestrel Grove’ in Bushey Heath and Bushey House in the village are now both private nursing homes but in 1914 they were occupied by wealthy families. Walter Burgh Gair, a banker and a director of The Great Central Railway, with a railway engine named after him, owned ‘Kestrel Grove’. His son, Henry, a banker married to the great granddaughter of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, enlisted with the Dorsetshire Regiment and served on the Western Front. He died of wounds on 15 May 1918.

Kestrel Grove

‘Bushey House’ was owned by Edward Hedley Cuthbertson of the Stock Exchange, whose two sons died in the war. His eldest son, Edward, enlisted in 1914 and served in France. He was twice invalided out before being sent to Mesopotamia, where he died in hospital in 1917. Hugh, his younger brother, was killed in action in France a year later.

These are just a few of the servicemen who lived in the mansions of Bushey but who lived in houses such as ‘Wentworth’ and ‘Inglewood’ in The Avenue, ‘Wayside’ and ‘The Sheiling’ in Grange Road, ‘Burnage’ in Bushey Grove Road and ‘Finch Cottage’ on Finch Lane?

The Sheiling

Who were the servicemen who lived at ‘Grove Cottages’ in Falconer Road, in ‘The Bungalow’ in Bournehall Road, at ‘Ivy House’ on the High Street and at ‘Cleveland’, now part of St Hilda’s School? Who enlisted from ‘Caroline Cottages’ in Oxhey and ‘Silverstone’ in Capel Road? Who was the famous bell-ringer who lived at ‘Alderbury’ in Oxhey Avenue and died in 1918?

Alderbury, Oxhey Avenue

The alehouse keeper of The Royal Oak on Sparrows Herne lost a son in the war and Bushey Heath also had fatalities.

The Royal Oak

Families living at ‘The Wintons’ and ‘Powis Court’ in The Rutts and the occupants of ‘Alpha Cottage’, ‘Eton Cottage’, ‘Chester Cottage’ on the High Road and ‘Itaska Cottages’ in Windmill Lane all received the dreaded yellow telegrams.

The majority of small terraced houses and cottages in Bushey and Oxhey did not have names but there were 11 fatalities in School Lane and 14 in Vale Road. New Bushey, later called Oxhey Village, was built for railway workers and was home to many young families. This area was one of the hardest hit with 15 fatalities in Villiers Road and 20 in Upper and Lower Paddock Roads.

180 houses in Bushey and Oxhey have been identified as the homes of servicemen who died during the war and there are many more that have been demolished or cannot now be traced. In addition, The Royal Masonic School in The Avenue, a significant part of the Bushey community during the war years, recorded 111 former pupils and staff who died on active service.

As part of the Bushey First World War Commemoration the present occupants of the houses where servicemen died will be invited to place a temporary plaque in their window or on their front gate in remembrance of those who made the ultimate sacrifice. Perhaps your house will be one of these.

The war affected every family in some way and men volunteered or enlisted from most homes in the area. Come to the exhibition ‘Bushey during the Great War: A Village Remembers’. Read the stories of those who died and those who survived. Find out who lived in your house in 1918 and discover if he served in the First World War.

Why did they go to war?

The Ibbott family lived at ‘Osborne Villa’, 57 Chalk Hill, Oxhey, a house high on the bankside on the corner of Villiers Road, which still stands today. Arthur Pearson Ibbott was a secretary and accountant to an investment company and he established a small independent Baptist Chapel in Oxhey, where he became the superintendent. His daughter, Grace, was an art student and all his sons attended Watford Grammar School for Boys.

The Ibbott Family in about 1914

L to R Claude Gordon, Bertram Charles, Grace Victoria, Harold William, Victoria, Arthur Pearson Ibbott, Arthur David

When war was declared, Arthur David Ibbott, his eldest son, immediately enlisted as Private 26046 with the Bedfordshires, later transferring to the Loyal North Lancashire Regiment. He was killed in action on 3 September 1916, aged 25. His younger brother, Bertram Charles Ibbott, joined the Machine Gun Corps as Private 85380 and died of wounds on 16 July 1917, aged 21.

Arthur David Ibbott has no known grave and is commemorated on the Thiepval Memorial to the Missing in Belgium, which bears the names of more than 72,000 officers and men, the majority of whom died between July and November 1916.

In 2006, James de Souza, great grandson of Claude Ibbott, went with a school party from Watford Grammar School for Boys to visit the battlefields of Ypres and the Somme. James, aged fourteen at the time, described finding the name of Arthur David Ibbott, his great grand uncle, on the Thiepval Memorial:

As I walked up the hill to the memorial I thought about what I expected to see. Because the name I was looking for was a relation of mine, someone I shared a bond with, I saw it as being special, not just for me, but for everyone. Part of me expected his name to stand out from the rest, perhaps in bolder writing or highlighted, but of course, it didn’t. His name was on face 11A of the memorial, in the second column, near the centre, just another name in a sea of soldiers to be remembered.

In 1919 Arthur Pearson Ibbott, my great, great grandfather, in his grief at the loss of two of his sons, wrote ‘In Darkest Christendom’, a book dedicated to their memory. As we stood by the Thiepval Memorial to the Missing, this extract was read out and I thought about the death of Arthur David Ibbott and how it had affected generations of his family right down to me:

‘My three sons of military age, loathing war like the devil, offered themselves. The revulsion of sentiment, if it can be called revulsion, which led these peace-loving lads to volunteer for war, is easily explained. They were simply satisfied that it was Britain’s duty to adopt the attitude she did, and, that being so, they must not leave it to others, they must offer themselves. Of the two who were accepted, the elder one trained and fought, and kept continually in touch with home, till there came a long spell with no letters, and then an official intimation that he had been posted as ‘missing’ after a certain engagement. For ten long months hope struggled against despair, till we had to admit the reasonableness of the presumption finally taken by the authorities that he had been killed. Then, as we meekly bowed our heads to the will of God, on a bright summer afternoon when everything spoke of peace and our hearts seemed for a moment to have found rest, came the dreaded yellow envelope from the Field Post Office, with the news that the younger one had been struck by a shell, and breathed his last ere the day was out.’

Courtesy of James de Souza of Oxhey and Jill Ibbott of Watford Heath, daughter-in-law of Claude Gordon Ibbott, the youngest member of the Ibbott family.

Poppies of Remembrance

Tucked away quietly in Bushey Heath is a magnificent garden that is open daily to the public. It is the garden of Reveley Lodge, 88 Elstree Road, a Victorian house bequeathed to Bushey Museum in 2003. Nicholas Boyes, the professional gardener, has recently planted a swathe of Flanders poppy seeds there in memory of two young men, from very different backgrounds, who once lived on the Reveley estate and died for their country. The poppies will bloom for the first time in August 2014, when the Bushey Commemoration Project holds its exhibition, ‘Bushey during the Great War: A Village Remembers’.

Edmund Johnson was the eldest child of a wealthy London tinplate manufacturer, who purchased Reveley Lodge, a large country house with eighteen rooms, in 1902. Edmund was then fourteen and had just started boarding at Rugby, the public school in Warwickshire, where he joined the school Cadet Corps. His younger sisters, Barbara and Helen, were taught by a governess at home. During the school holidays Edmund played tennis on the lawn and enjoyed the woodland area in the four-acre garden. In 1909 his father decided to let Reveley Lodge to tenants and the Johnson family moved briefly back to London before settling at Braithwaite Fold in Windermere, Westmoreland.

When war broke out, Edmund volunteered immediately, enlisting on 4 September 1914 as Private 33637 with the Public Schools Battalion of the Middlesex Regiment. Aged 26, 5’8″ in height, with ‘a light complexion, blue eyes and light brown hair’, he wore spectacles and gave his occupation as ‘a manufacturer’. He trained at various army camps in England, wearing civilian clothing and drilling with broomsticks, lengths of wood or gas piping until military equipment arrived. In May 1915, Edmund was discharged from military service with signs of tuberculous pleurisy so when his Battalion was sent to Boulogne on 17 November that year, he was unable to join them. Later, with his health restored and keen to serve abroad, he re-enlisted as Private G/40280 with the 1st Battalion of The Queen’s (Royal West Surrey Regiment). He fought with them on the Western Front until he was killed in action on 12 April 1918, at the aged of 31. He is remembered with honour on the Ploegsteert Memorial to the Missing in Belgium.

Next to Reveley Lodge stands a row of ‘two-up two-down’ cottages. Built earlier than the big house, they were purchased and became part of the estate, rented out to servants or tenants. From about 1905, 7 Reveley Cottages was home to Charlie Payne, the eldest of seven children. His father was a sewage farm labourer and Edmund Johnson’s father was his landlord. Charlie was a pupil at Ashfield School in School Lane, Bushey and by the time he was fourteen, he was employed as a grocer’s assistant. If Charlie and Edmund ever met, they are unlikely to have had much in common.

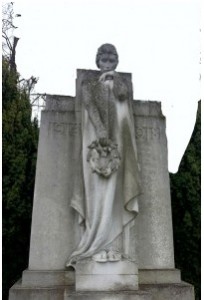

When war was declared, Charlie enlisted immediately as a volunteer with his school friends, Arthur Baldock and George Rodway, from Windmill Lane. They all joined the Rifle Brigade and served in France and Flanders. Charlie, Rifleman S/13021, was killed in action on 7 January 1916, aged 20, and is remembered with honour at the Menin Gate Memorial to the Missing at Ypres in Belgium. His school friend, George Rodway, died of wounds in France on 5 May 1917, aged 20. Charlie and George are both commemorated on the Bushey Memorial on Clay Hill and at St Peter’s Church, Bushey Heath.

A Dead Man’s Penny

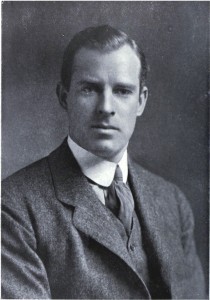

Ernest Farmer, an agricultural labourer and shepherd, lived at Bushey Hall Farm Cottages, Bushey Mill Lane. He was 5ft 4 inches tall with a fresh complexion, brown eyes, dark brown hair and a slight curvature of the spine.

When war broke out, he enlisted as Private 43078 with the 6th Battalion of the Northamptonshire Regiment and served in France and Flanders. He was killed in action on 17 February 1917 and is buried at Regina Trench Cemetery, Grandcourt, on the Somme.

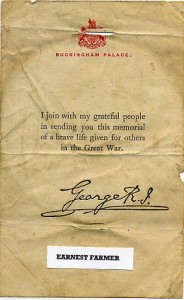

After the war, Ernest Farmer’s family, like those of other service men and women who died, was sent a memorial plaque, commonly known as a ‘Dead Man’s Penny’.

The medallion, made of bronze gun metal, was 12 centimetres (5 inches) in diameter and 1,355,000 plaques were issued using 450 tonnes of bronze. The design incorporated symbols and words including Britannia holding an oak wreath, an imperial lion, two dolphins representing Britain’s naval forces, a rectangular tablet containing the deceased’s name (no rank was given as all men were considered to be equal) along with the words, ‘He died for freedom and honour’ around the perimeter. Only 600 were issued for women with the words, ‘She died for freedom and honour’. The Memorial Plaque was accompanied by a Memorial Scroll, a letter from Buckingham Palace and sometimes a letter from the commanding officer was included.

In 1922, Ernest Farmer’s name was engraved alongside 157 others on the war memorial erected at Clay Hill in Bushey. This monument, designed by Sir William Reid Dick, was brought from London by horse and cart driven by Ernest’s brother-in-law, Albert Rolls of Fearnley Street, Watford. Ernest Farmer’s nephew, Peter George Rolls, now has his Dead Man’s Penny.

Jackie Taslaq

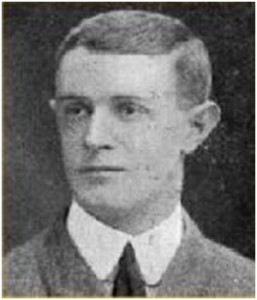

Lieutenant Arthur Langton Airy (Herkomer student)

Over a period of twenty years, Hubert Herkomer taught about 600 students at his Art School in Bushey village. By 1914, the school had been closed for ten years but a number of former students settled in the village and the surrounding area. When Arthur Langton Airy was killed in France in 1915, friends remembered him and he was named as a Herkomer student in the Bushey Parish Magazine alongside other war casualties.

Over a period of twenty years, Hubert Herkomer taught about 600 students at his Art School in Bushey village. By 1914, the school had been closed for ten years but a number of former students settled in the village and the surrounding area. When Arthur Langton Airy was killed in France in 1915, friends remembered him and he was named as a Herkomer student in the Bushey Parish Magazine alongside other war casualties.

Arthur Langton Airy came from a distinguished family. His grandfather, Sir George Biddell Airy, was Astronomer Royal from 1835 to 1881. During his tenure of 46 years in that role he transformed the Observatory at Greenwich, establishing it as the location of the prime meridian.

Arthur Langton Airy

Arthur’s father, Dr Hubert Airy, was a physician and wrote one of the definitive papers on migraine. Anna Airy, Arthur’s cousin, was one of the first women officially commissioned as a war artist.

Arthur, born in about 1877, was the youngest of three children and inherited his mother’s maiden name of Langton. His eldest sister, Mary, was born in Lee, at that time in Kent, while Arthur and sister, Agnes, started life nearby in Kidbrooke, just a few miles from the Greenwich Observatory. By the time he was four, the family had moved to Eastbourne but there were strong family links with Suffolk so Arthur was sent to Eaton House, a private boarding school in Aldeburgh.

Arthur Langton Airy was a student at the Herkomer Art School in Bushey in 1896. After his studies he returned home to his parents, who were living in Woodbridge, Suffolk.

Dr Hubert Airy

In April 1900 Arthur was commissioned into the 3rd Battalion of the Northamptonshire Regiment and gained his Lieutenancy in November that year, serving with the Ist Battalion in South Africa. He left the army on the death of his father in 1903. That year he married Grace Wood at Easton in Suffolk and by 1911 they had settled in Worthing, where Arthur worked as an artist. Their two children, Hubert Arthur and Jack Langton, were both named after their grandparents. Between 1899 and 1912 Arthur was a member of the Ipswich Art Club.

He exhibited at the Royal Academy from 1904 until 1910, from Woodbridge in 1904, from London in1907 and from Worthing, Sussex in 1910.

At the outbreak of the First World War he offered his services again, re-enlisting in the Northampton Regiment in October 1914. Like countless other young men, he left his wife and children to serve his country. He was killed in action in the trenches east of Cuinchy in France on 11 January 1915, aged 39 and has no known grave. He is commemorated on the Le Touret Memorial to the Missing and on the Woodbridge Memorial in Suffolk.

Le Touret Memorial