A Remarkable Coincidence

When the Bushey First World War Exhibition, ‘ A Village Remembers’, was over in August 2014, Roger and I went on holiday to the Lake District. We stayed in a small guest house in Borrowdale at the foot of the Honister Pass, seven miles south of Keswick. Seatoller House, originally a small farm house, is over 300 years old and has been a guest house for more than 100 years. Its long tradition of warm hospitality and a friendly, informal atmosphere make it popular with walkers, artists, and those who want immediate access to the fells.

Seatoller House has visitors’ books dating back to 1900, which record the names of participants in the Man Hunts, created by a Cambridge undergraduate, G M Trevelyan, in 1898. Inspired by the great man hunt in Robert Louis Stevenson’s ‘Kidnapped’, this is a game of hare and hounds played out in the fells above Seatoller. On each of the three days of hunting, several members of the hunt, the ‘hares’, leave the house at 8 am, carrying scarlet sashes and hunting horns. The remainder of the party, the ‘hounds’, leave half an hour later. ‘Tally- ho!’ rings across the fells and the ‘hounds’ are expected to make full use of their hunting horns to attract attention and can be caught by touching. In 1901 the Hunt split in two – one organised from Trinity College, Cambridge, the other by C P Trevelyan. With a break for the two world wars, both Hunts continue from Seatoller House today.[1]

Intrigued by details of these Hunts in the visitors’ books, I could not resist looking further. On 22 July 1914, two weeks before Britain declared war, Leo Burley, a British diamond merchant living in Antwerp, stayed at Seatoller House with his wife, Anna, who was the niece of Professor Ludwig Knaus, a celebrated German artist (1829–1910). Leo Burley signed the visitors’ book and made this poignant entry:

‘Returned after an absence of more than 20 years to find the same unostentatious comfort and the same hospitable care, the same beauty of hill and valley, of rivulet and lake. The European capitals are seething with the violence of men’s passions; by the Danube the roar of Austrian artillery has already been heard – and the dark, silent fells around us remain in imperturbable calm’.

In 1914 Antwerp was ringed by Belgian forts and after the German invasion of Belgium in August that year, German troops besieged the city. Leo and Anna Burley’s house and all its contents were destroyed during the bombardment. They decided to make their home in England and never returned to Antwerp. During the war Leo served as a Special Constable and they both worked for Quaker Charities to relieve the sufferings of war victims. Leo died in Finchley in 1921 at the age of 48. During his life he had enjoyed many walking tours with his wife in the Black Forest, in Switzerland and in the Lake District, perhaps his favourite haunt.[2]

A few visitors stayed at Seatoller House during the First World War and as I turned the pages of the visitors’ book to July 1915, I spotted two signatures from Bushey.

Ancestry.com revealed that Edith Bateson and Anna Gayton were both artists and, as I later discovered, were on Bushey Museum’s list of Artists and Students resident in Bushey in 1915.

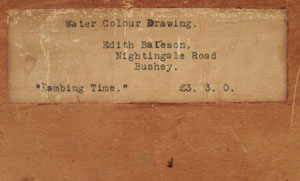

Edith Bateson, born in 1867, was the youngest daughter of William H Bateson, the Master of St John’s College, Cambridge. From 1891 she studied at the Royal Academy Schools, where she won three silver medals for sculpture. She was one of a group of women artists encouraged to take up sculpture at a time when modelling was done in clay before being cast in bronze. Prior to this, sculpture had been thought too physically demanding for women. One of Edith Bateson’s statues now stands in the library of Lady Margaret Hall at Oxford University. Later, she moved on to painting and by the time she came to Bushey in 1915, she was established as a professional artist at Robin Hood’s Bay in Yorkshire, part of the Fylingdale group. She exhibited four times at the Royal Academy, at many provincial galleries and at the International Society of Sculptors.

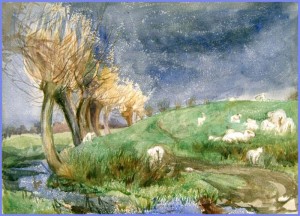

Her vibrant watercolour, ‘Lambing Time’, was painted while she was living in Nightingale Road, Bushey in 1918. It depicts the onset of an English Spring, with lambs and newly shooting willows under a blustery sky. The ‘modern’ feel and positive atmosphere perhaps accords with the imminent ending of the First World War. While in Bushey, Edith Bateson became part of the artistic colony and befriended Winifred, the younger sister of the artist, Kate Cowderoy, who lived at The Retreat, 5 Hillside Road. In 1919 Edith exhibited a sculpture of Winifred Cowderoy at the Autumn Exhibition of the International Society of Sculptors, Painters and Gravers in London.[3]

Anna Maria Gayton, about six year older than Edith, also studied at the Royal Academy Schools, where she too won prizes for sculpture in 1888 and 1890.[4] The youngest daughter of a solicitor, she lived in Much Hadham in Hertfordshire and the 1901 census shows Edith living with her there. Anna later acted as housekeeper for her older brother, a doctor and surgeon, who was Medical Superintendent of Surrey County Asylum.

Entries in the visitors’ book at Seatoller House produced some fascinating stories. As Roger and I signed our names, I mentioned Edith Bateson and Anna Gayton from the unique artists’ colony who stayed there in 1915 and added a link to Bushey Museum and Art Gallery.

Dianne Payne

[1] Seatoller House – Published by The Lake Hunts Ltd [2] “Harvard College Class of 1900 fourth report”, www.archive.org/stream/harvardcol.. [3] Edith Bateson Mapping the Practice and Profession of Sculpture in Britain and Ireland 1851-1951, University of Glasgow History of Art and HATII, online database 2011 [4] ‘Anna Maria Gayton’, Mapping the Practice and Profession of Sculpture in Britain and Ireland 1851-1951, University of Glasgow History of Art and HATII, online database 2011

The Real Story behind the Christmas Truce 1914

The Christmas Truce has become one of the most famous and mythologised events of the First World War. But what was the real story behind the truce? Why did it happen and did British and German soldiers really play football in no-man’s land?

Late on Christmas Eve 1914, men of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) heard German troops in the trenches opposite them singing carols and patriotic songs and saw lanterns and small fir trees along their trenches. Messages began to be shouted between the trenches. The following day, British and German soldiers met in no man’s land and exchanged gifts, took photographs and some played impromptu games of football. They also buried casualties and repaired trenches and dugouts. After Boxing Day, meetings in no man’s land dwindled out.

The truce was not observed everywhere along the Western Front. Elsewhere the fighting continued and casualties did occur on Christmas Day. Some officers were unhappy at the truce and worried that it would undermine fighting spirit.

After 1914, the High Commands on both sides tried to prevent any truces on a similar scale happening again. Despite this, there were some isolated incidents of soldiers holding brief truces later in the war, and not only at Christmas. In what was known as the ‘Live and Let Live’ system, in quiet sectors of the front line, brief pauses in the hostilities were sometimes tacitly agreed, allowing both sides to repair their trenches or gather their dead.

Amanda Mason, Historian

Imperial War Museum

Percy Tarver of Bushey gives his account of the Christmas Truce

‘We inhabited a house close to our old weaving factory, with a broken bridge and a mill stream and canal under its windows. The Colonel and officers were below and we signallers packed into a little backstairs room overlooking the stream. Twelve of us in one room, and we filled it with our muddy packs and kit. Christmas parcels, plum pudding, cake and chocolates were going begging for a time but nothing was wasted although we had three regimental puddings extra from various ladies in Kensington, and we boiled them in our mess tins, cut in halves or ate them cold. The weather turned Christmassy.

Meanwhile my half battalion went into the trenches, different ones this time and found themselves in an awful state, with terrible entrances and water and mud in places to the waist. There the poor boys stayed, but luckily for them the Germans began Christmassing on 24th, and actually waved little illuminated Christmas trees, and stopped firing. (Their guns had stopped replying to ours for some time, but their machine guns and rifle fire was very heavy. I don’t know actually when or how the truce began but some say a few Germans came out unarmed and shouted, ‘Don’t shoot for two days and we won’t.’) Anyway, on Christmas morning both sides came out, and met and ‘swopped’ cigarettes. Lots of them spoke English. All the time we and they were busy taking advantage of the peace to repair trenches, bring up fuel and boards and ammunition. This went on for two days and became rather embarrassing to our chiefs, I should think. They even talked of arranging a football match. Finally the men were ordered back to the trenches’.

Percy Tarver, London Territorials (Kensingtons)

West Herts and Watford Observer, 9 January 1914.

A few letters from the front line refer directly to football in no man’s land

‘On Christmas Day one of the Germans came out of the trenches and held his hands up. Our fellows immediately got out of theirs, and we met in the middle, and for the rest of the day we fraternised, exchanging food, cigarettes and souvenirs. The Germans gave us some of their sausages, and we gave them some of our stuff. The Scotsmen started the bagpipes and we had a rare old jollification, which included football in which the Germans took part. The Germans expressed themselves as being tired of the war and wished it was over. They greatly admired our equipment and wanted to exchange jack knives and other articles. Next day we got an order that all communication and friendly intercourse with the enemy must cease but we did not fire at all that day and the Germans did not fire at us.’

Company-Sergeant Major Frank Naden, 6th Cheshire Territorials

Evening Mail, Newcastle, 31 December 1914

‘A brief sad episode, but a small light of humanity in the darkness of war’.

Don Shaw, Mickleover, Derbyshire.

Letter to The Times, 13th December 2014

For further examples of letters about the Christmas Truce from local newspapers see: www.christmastruce.co.uk

Plaques as Commemoration

In 1914, ‘Lime Kiln Cottage’ stood close to the Bushey railway arches, near the kilns where local chalk was once burned to provide lime. Up the hill towards Bushey village, just beyond ‘The Merry Month of May’ alehouse, was a row of cottages with the intriguing name ‘Crook Log’. Both ‘Lime Kiln Cottage’ and ‘Crook Log’ were demolished decades ago but this year the Bushey First World War Commemoration Project will focus a spotlight on them and other houses in the area as the servicemen who died in the war are remembered . ‘Lime Kiln Cottage’ was home to the Drake family, who lost two sons, and five servicemen living at ‘Crook Log’ gave their lives for their country.

Crook Log

The communities of Bushey and Oxhey in 1914 included wealthy land owners, labourers and railway workers. Some who enlisted for war service lived in grand mansions and others in tiny cottages. More than three hundred and fifty did not come home.

Bushey Manor House

Bushey Manor House, which stood on the site now occupied by The Bushey Academy, was owned by Charles Gabain, a retired French coffee importer, Bushey Urban District Councillor and JP, who lost his only son in the war. Captain William Gabain, who was awarded the Military Cross for gallantry, was last seen in 1918 ‘in a sunken road holding on with a handful of men practically surrounded by infinitely superior numbers of the enemy’. He was reported missing but it was nearly a year before his family accepted that he had died and his obituary appeared in The Times.

Hartsbourne Manor

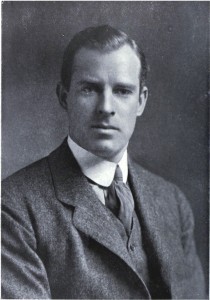

‘Hartsbourne Manor’, now a golf club, was owned in 1914 by the American actress, Maxine Elliot, who was said to be engaged to a New Zealander, Anthony Wilding, a former Wimbledon Tennis Champion and frequent visitor to her home. In May 1915, Maxine Elliot was working for the Red Cross, the first American to do so. She was travelling along the waterways of Belgium, providing starving refugees with food and medical attention, when she heard that Captain Wilding had been killed in action at the battle of Aubers Ridge in France. The man she hoped would join her permanently at ‘Hartsbourne Manor’ had perished.

Maxine Elliot Anthony Wilding

‘Kestrel Grove’ in Bushey Heath and Bushey House in the village are now both private nursing homes but in 1914 they were occupied by wealthy families. Walter Burgh Gair, a banker and a director of The Great Central Railway, with a railway engine named after him, owned ‘Kestrel Grove’. His son, Henry, a banker married to the great granddaughter of Samuel Taylor Coleridge, enlisted with the Dorsetshire Regiment and served on the Western Front. He died of wounds on 15 May 1918.

Kestrel Grove

‘Bushey House’ was owned by Edward Hedley Cuthbertson of the Stock Exchange, whose two sons died in the war. His eldest son, Edward, enlisted in 1914 and served in France. He was twice invalided out before being sent to Mesopotamia, where he died in hospital in 1917. Hugh, his younger brother, was killed in action in France a year later.

These are just a few of the servicemen who lived in the mansions of Bushey but who lived in houses such as ‘Wentworth’ and ‘Inglewood’ in The Avenue, ‘Wayside’ and ‘The Sheiling’ in Grange Road, ‘Burnage’ in Bushey Grove Road and ‘Finch Cottage’ on Finch Lane?

The Sheiling

Who were the servicemen who lived at ‘Grove Cottages’ in Falconer Road, in ‘The Bungalow’ in Bournehall Road, at ‘Ivy House’ on the High Street and at ‘Cleveland’, now part of St Hilda’s School? Who enlisted from ‘Caroline Cottages’ in Oxhey and ‘Silverstone’ in Capel Road? Who was the famous bell-ringer who lived at ‘Alderbury’ in Oxhey Avenue and died in 1918?

Alderbury, Oxhey Avenue

The alehouse keeper of The Royal Oak on Sparrows Herne lost a son in the war and Bushey Heath also had fatalities.

The Royal Oak

Families living at ‘The Wintons’ and ‘Powis Court’ in The Rutts and the occupants of ‘Alpha Cottage’, ‘Eton Cottage’, ‘Chester Cottage’ on the High Road and ‘Itaska Cottages’ in Windmill Lane all received the dreaded yellow telegrams.

The majority of small terraced houses and cottages in Bushey and Oxhey did not have names but there were 11 fatalities in School Lane and 14 in Vale Road. New Bushey, later called Oxhey Village, was built for railway workers and was home to many young families. This area was one of the hardest hit with 15 fatalities in Villiers Road and 20 in Upper and Lower Paddock Roads.

180 houses in Bushey and Oxhey have been identified as the homes of servicemen who died during the war and there are many more that have been demolished or cannot now be traced. In addition, The Royal Masonic School in The Avenue, a significant part of the Bushey community during the war years, recorded 111 former pupils and staff who died on active service.

As part of the Bushey First World War Commemoration the present occupants of the houses where servicemen died will be invited to place a temporary plaque in their window or on their front gate in remembrance of those who made the ultimate sacrifice. Perhaps your house will be one of these.

The war affected every family in some way and men volunteered or enlisted from most homes in the area. Come to the exhibition ‘Bushey during the Great War: A Village Remembers’. Read the stories of those who died and those who survived. Find out who lived in your house in 1918 and discover if he served in the First World War.

Poppies of Remembrance

Tucked away quietly in Bushey Heath is a magnificent garden that is open daily to the public. It is the garden of Reveley Lodge, 88 Elstree Road, a Victorian house bequeathed to Bushey Museum in 2003. Nicholas Boyes, the professional gardener, has recently planted a swathe of Flanders poppy seeds there in memory of two young men, from very different backgrounds, who once lived on the Reveley estate and died for their country. The poppies will bloom for the first time in August 2014, when the Bushey Commemoration Project holds its exhibition, ‘Bushey during the Great War: A Village Remembers’.

Edmund Johnson was the eldest child of a wealthy London tinplate manufacturer, who purchased Reveley Lodge, a large country house with eighteen rooms, in 1902. Edmund was then fourteen and had just started boarding at Rugby, the public school in Warwickshire, where he joined the school Cadet Corps. His younger sisters, Barbara and Helen, were taught by a governess at home. During the school holidays Edmund played tennis on the lawn and enjoyed the woodland area in the four-acre garden. In 1909 his father decided to let Reveley Lodge to tenants and the Johnson family moved briefly back to London before settling at Braithwaite Fold in Windermere, Westmoreland.

When war broke out, Edmund volunteered immediately, enlisting on 4 September 1914 as Private 33637 with the Public Schools Battalion of the Middlesex Regiment. Aged 26, 5’8″ in height, with ‘a light complexion, blue eyes and light brown hair’, he wore spectacles and gave his occupation as ‘a manufacturer’. He trained at various army camps in England, wearing civilian clothing and drilling with broomsticks, lengths of wood or gas piping until military equipment arrived. In May 1915, Edmund was discharged from military service with signs of tuberculous pleurisy so when his Battalion was sent to Boulogne on 17 November that year, he was unable to join them. Later, with his health restored and keen to serve abroad, he re-enlisted as Private G/40280 with the 1st Battalion of The Queen’s (Royal West Surrey Regiment). He fought with them on the Western Front until he was killed in action on 12 April 1918, at the aged of 31. He is remembered with honour on the Ploegsteert Memorial to the Missing in Belgium.

Next to Reveley Lodge stands a row of ‘two-up two-down’ cottages. Built earlier than the big house, they were purchased and became part of the estate, rented out to servants or tenants. From about 1905, 7 Reveley Cottages was home to Charlie Payne, the eldest of seven children. His father was a sewage farm labourer and Edmund Johnson’s father was his landlord. Charlie was a pupil at Ashfield School in School Lane, Bushey and by the time he was fourteen, he was employed as a grocer’s assistant. If Charlie and Edmund ever met, they are unlikely to have had much in common.

When war was declared, Charlie enlisted immediately as a volunteer with his school friends, Arthur Baldock and George Rodway, from Windmill Lane. They all joined the Rifle Brigade and served in France and Flanders. Charlie, Rifleman S/13021, was killed in action on 7 January 1916, aged 20, and is remembered with honour at the Menin Gate Memorial to the Missing at Ypres in Belgium. His school friend, George Rodway, died of wounds in France on 5 May 1917, aged 20. Charlie and George are both commemorated on the Bushey Memorial on Clay Hill and at St Peter’s Church, Bushey Heath.