Archive

“Lads, You’re Wanted. Come and Die”

Take your risk of life and death

Underneath the open sky.

Live clean or go out quick-

Lads, you’re wanted. Come and die.

From the poem ‘Recruiting’ by E. A. Mackintosh

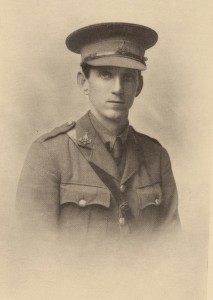

In June 2000, as part of their academic curriculum, 65 girls from The Royal Masonic School at Rickmansworth, together with a few members of Staff, made a battlefield tour of the Somme. Before they went each of the girls had been given a booklet which explained the background of the battle, provided a map of the action on the opening day (July 1st 1916), and included some of the more powerful First World War poems. It also included a section on the 111 Old Boys of the School at Bushey who had lost their lives during the war, many of them on the Western Front. Each of the girls was allocated the name of one of these Old Boys together with brief biographical details and – for most of them – a photograph copied from those which the boys had been encouraged to send to the School when they joined up.

We are grateful to one of the members of Staff, Mrs Anne-Georgina Barnes, for the following account of the visit:

“This year as a joint venture, the History and English Departments of The Royal Masonic School, Rickmansworth combined to take the GCSE Year 10 History and English girls and Year 12 Historians to the Somme battlefields. Our purpose was two-fold: firstly, the academic. Clearly, this linked various academic disciplines. In Year 10 the girls study both the History of the First World War, particularly focussing on the Western Front, together with the poetry produced by Owen, Sassoon and the like. For ‘A’ Level the girls look at the 19th century, finishing with the outbreak of war in 1914, and so for them this was a fitting chronological end to their ‘A’ Level studies. Our Chaplain, Miss Horton, joined us for a Memorial Service with which everyone could identify and so was provided a religious and moral cross-curricular link. Our second purpose was to commemorate the dead of The Royal Masonic School for Boys in Bushey. As we move into a new century it is up to the younger generation to make a better world but, before one can do that, we have to remember the past. The First World War is now eighty years ago and to our girls almost as far in the past as the Tudors, so we very much wanted to draw their attention to the real human perspective.

We left School at 5 am, so some of us rose before 4 o’clock, although thankfully at this time of year it is beginning to get light. The coaches took us to the Eurotunnel, which to some of us was a novel experience but did away with the hazard of sea-sickness. How much worse it must have been for Tommy Atkins, crossing the seas in his boat! Once in France, we drove from Calais to the little town of Albert on the Somme, where we visited the Musee des Abris (Museum of the Shelter). Inside was a fascinating collection of memorabilia; sepia photographs and cartoons, rusting helmets, tins of gas ointment and assorted equipment, faded uniforms and buttons, drawings and copperplate letters as well as various weapons. There were also posed mannequins dressed in different uniforms which gave us a moving glimpse into trench life eighty years ago. They stood in their dugouts surrounded by the paraphernalia of war, reading letters, preparing to attack, killing rats.

Once back outside the museum, we drove to Delville Wood and the South African Memorial, where we saw our first mass cemetery. Perspective drew the simple white tombstones into complex geometric patterns as we looked down the rows, the formality offset by flowers, particularly roses. Most tombs had a brief identification, a name, a rank and badge, but so many just read ‘A Soldier of the Great War, Known unto God’. After lunch we moved on to Peronne, where our two guides joined us, and then we drove further into the Somme fighting area. We went first to the Locnagar crater at La Boisselle. This was the result of sapping on the morning of July 1st 1916 and thus started the offensive of the Somme battle. The crater is still twenty feet deep today, but in 1916 it blew forty feet down and completely annihilated a German trench system. The girls were stunned at this evidence of warfare and listened carefully as the guides told them about the first morning of the battle.

Once back outside the museum, we drove to Delville Wood and the South African Memorial, where we saw our first mass cemetery. Perspective drew the simple white tombstones into complex geometric patterns as we looked down the rows, the formality offset by flowers, particularly roses. Most tombs had a brief identification, a name, a rank and badge, but so many just read ‘A Soldier of the Great War, Known unto God’. After lunch we moved on to Peronne, where our two guides joined us, and then we drove further into the Somme fighting area. We went first to the Locnagar crater at La Boisselle. This was the result of sapping on the morning of July 1st 1916 and thus started the offensive of the Somme battle. The crater is still twenty feet deep today, but in 1916 it blew forty feet down and completely annihilated a German trench system. The girls were stunned at this evidence of warfare and listened carefully as the guides told them about the first morning of the battle.

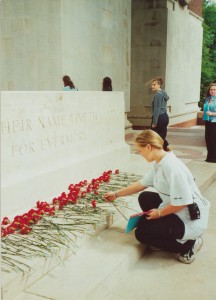

Then to the Thiepval Memorial whose marble walls have the names of 73,000 men inscribed thereon. These were the men whose bodies were never found or identified satisfactorily. The girls had each been linked with a partner, an Old Boy from our brother School at Bushey. Our War Memorial shows that one hundred and eleven Old Masonic Boys died during the Great War, many of whom fell during the Somme battles. We commemorated all those who fell in France or nearby, to equate the number of soldiers with the girls, although the resting places of the other soldiers are much more scattered, from Plymouth to Jerusalem. At Thiepval we held our Memorial Service, conducted by our Chaplain, and laid red carnations at the foot of the memorial stone. There were few dry eyes when we had finished, and the girls realised that the names were not just anonymous, but very real men, and they appreciated the tragedy of their death.

Then to the Thiepval Memorial whose marble walls have the names of 73,000 men inscribed thereon. These were the men whose bodies were never found or identified satisfactorily. The girls had each been linked with a partner, an Old Boy from our brother School at Bushey. Our War Memorial shows that one hundred and eleven Old Masonic Boys died during the Great War, many of whom fell during the Somme battles. We commemorated all those who fell in France or nearby, to equate the number of soldiers with the girls, although the resting places of the other soldiers are much more scattered, from Plymouth to Jerusalem. At Thiepval we held our Memorial Service, conducted by our Chaplain, and laid red carnations at the foot of the memorial stone. There were few dry eyes when we had finished, and the girls realised that the names were not just anonymous, but very real men, and they appreciated the tragedy of their death.

Thoughtfully, we moved on to see the remains of the trenches at Beaumont-Hamel. We walked along the winding trenches and looked across the rough ground of No Man’s Land to the distant German lines. Crouching down in the worn trenches, you could just begin to imagine what it was like for the soldiers concerned. The weather was very dry that day and had been so for some time, but even so there was mud in the bottom of the trenches-what it must have been like during the battle defies description. The air at Beaumont-Hamel was full of bird-song as we thought of the carnage that had happened where we walked. Behind us was the memorial to the Newfoundlanders with their long list of names and caribou emblem: they too had their tragedies.

After this we began the long journey home, retracing our steps through France, the tunnel and eventually back to School. We arrived back at 10.30 pm, very tired but interested and moved by our experiences. As our Memorial Service said, “We will remember them”.

After this we began the long journey home, retracing our steps through France, the tunnel and eventually back to School. We arrived back at 10.30 pm, very tired but interested and moved by our experiences. As our Memorial Service said, “We will remember them”.

After their visit the girls were asked to write an account if the day and readers may be interested in extracts from some if the impressions recorded if their experience:

“The most interesting part of the Museum was the wax figures showing different scenes from the war. Some were quite frightening, especially that of a man killing rats the size of rabbits.”

“In the cemetery were 2000 gravestones many of which were unnamed and simply said ‘A soldier of the Great War. Known unto God’. The reality of the number of lives lost only just began to sink into me. I thought it was so sad that so many people gave their lives and they cannot even have their names on their gravestone.”

“It was wonderful to see all the graves being kept in perfect condition, me grass being regularly cut, and beautiful flowers on all the graves, including those which were unnamed.”

“Everyone on me trip had been allocated the name of a soldier. These men were Old Boys from the School at Bushey. It was a very good idea and it gave us a more personal approach to remembering me men who gave their lives. The name of me soldier I was allocated was C. W. Britten. At me ceremony we each had to place a carnation on the memorial as me name of our Old Boy was read out. This, I felt, was the most worthwhile part of the trip.”

C. W. Britten

[Charles Wells Britten was born in 1887 and was in Headmaster’s House at School from 1898 to 1903 when he left to become a clerk in William Forbes & Co., London. for whom he worked for a while in China. He joined up in 1914 and was rapidly promoted, becoming a Major in the Royal Field Artillery. He fought on the Somme and at Memetz; Wood and was killed by shell fire while putting out fires in April 1917, aged 30. He is buried at Bedford House cemetery at Zillebeke, near Ypres -Ed.]

“The thing that struck me most about the trenches was the silence. All we could hear were the larks.”

“The Old Boy I remembered was E. Richardson and, although I know little about him, it was nice to be able to remember someone who may have no-one else to remember him.”

E. Richardson

[Ewart Richardson was born in 1881 and at School was in Lathom House from 1892 to 1899. When he left School he became a solicitor and joined up in 1915, becoming a Second Lieutenant in the 4th Yorkshire Regiment. He went out to France in May 1916 and was killed in the fighting at Martinpuich in September. He was 35 years old. His name is on the Thiepval Memorial.-Ed.]

“I did not realize how big No Man’s Land was and in many places there was still some barbed wire sticking up.”

“Seeing the trenches made you really imagine what it was like and, although I shall never get the real experience, seeing the damage caused was enough to make me pleased I was not alive then.”

“It was not the black and white photographs or the letters from the soldiers which made the trenches reality for us. It was the never-ending supply of mouldy helmets, guns, knives, swords, both British and German.”

“I can distinctly remember a picture of a smiling young man in the display cabinet with his belt, buckle, and knife just below it. There was a strange sensation as we passed that display because we had seen his face which we knew would not have been smiling when the shell had exploded near him.”

“My favourite part of the trip occurred at the Thiepval Memorial. We were each allocated an Old Boy from The Royal Masonic School who had died during the war. We then held our own private Memorial Service during which all the men’s names were called out and each of us in turn placed a flower on a stone step of the Memorial. It was very touching and most of us were in tears by the end. So many names; so many lives lost.”

The article is re-published from The Old Masonians’ Gazette, May 2001 by kind permission of the Editor.

« Bertram Prewett – Renowned Bushey Bell Ringer / Bernard Thomas Stebbeds »